EUA - Hawai (Oahu) - Granja Orgánica Ma'o: Cultivando Alimento y Capacitando Jóvenes

- Autor: Regina Gregory

El proceso de colonización de Hawai resultó en la pérdida de acceso a aguas y tierras por parte de los indígenas. También resultó en pérdidas culturales y de auto-gobierno. El distrito Wai’anae en particular es conocido como una región con pocas oportunidades económicas y muchos problemas sociales. Con su granja orgánica y varios programas culturales y educativos, que incluyen oportunidades económicas para estudiantes, MA’O ayuda a mejorar la seguridad alimentaria, así como el bienestar económico y social de esta comunidad marginada.

Geography

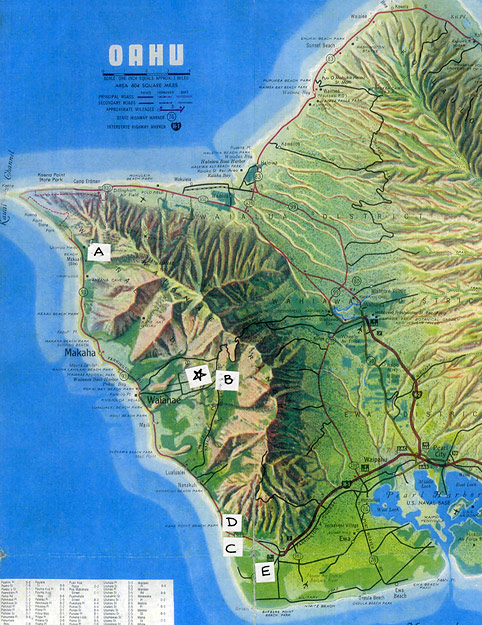

Mala 'Ai 'Opio ("youth food garden" in Hawaiian, MA'O for short) is a 5-acre farm in Lualualei Valley, the largest valley on the western coast of O'ahu, Hawai'i. It is near the town of Wai'anae (see star on the map below).

Wai'anae District comprises the watershed between Nanakuli and the northwest tip of the island. Traditionally the Wai'anae Moku (land division) also included a narrow strip of land in the center which reached over the Wai'anae mountain range, through central O'ahu and up to the top of the Ko'olau mountains.

The area is hot and receives little rainfall (30-40 inches) compared to the rest of the island. Even in the upper valleys the rainfall is only 40-60 inches. Many of the streams and springs that once flowed year-round are now intermittent or entirely dry.

History

Wai'anae is thought to derive its name from the anae, or large mullet, that thrived in the coastal waters and in a man-made fishpond near Pokai Bay. All along the coast fish were plentiful, so there were many early Polynesian settlements along the shore. In the lower valleys, settlements and agricultural areas were limited to places near streams and springs. The wetter upper valleys were more densely populated.

According to the MA'O website (http://www.maoorganicfarms.org), the district was "a self-sufficient region that produced adequate amounts of food for its people while managing its land and water resources sustainably."

Negative Tipping Point

Like many problems in Hawai'i (and indeed around the world), a major "negative tip" was colonization. When Captain Cook arrived in Hawai'i in the late 1700s, followed by missionaries and businessmen, they brought with them diseases that killed about three quarters of the local population. It is estimated that the population of Wai'anae District fell from 4,000-6,000 to 500 between 1770 and 1870.

The sandalwood trade bound for China caused widespread deforestation, and diverted farmers from tending their crops. This was followed by cattle ranching and sugar plantations. Over the years these industries came to control much of the land and water.

Thus Hawaiians became dispossessed of their lands and water. They also lost their nationhood, as a group of U.S. sugar growers and businessmen overthrew the government in 1893 and Hawai'i was annexed by the U.S. in 1898. Or, as more accurately stated by Wai'anae native and member of the MA'O Board of Directors William Aila, Jr., "Queen Liliuokalani ceded Hawaii temporarily to the US, until such time that an investigation was done on the US involvement in the revolution by US sugar planters and businessmen in 1893 and illegally annexed in 1898."

To "rehabilitate" the native population by returning them to the land, the Hawaiian Homestead Act was passed by the U.S. Congress in 1920, designating about 200,000 acres of land for Native Hawaiians, somewhat similar to Indian reservations but divided into individual lots. The homesteads at Wai'anae, Lualualei, and Nanakuli attracted a large number of Hawaiians to the Wai'anae District.

Unfortunately, of the 2,000 acres designated as Hawaiian Homelands in the Wai'anae and Lualualei Valleys, 1,700 acres were taken by executive order in the early 1930s for the purpose of a Navy ammunition depot and radio transmitter facility. During World War II the U.S. Army took control of the entire Makua Valley, and to this day still uses it for target practice. According to the Department of Hawaiian Homelands website (http://hawaii.gov/dhhl), 34% of the land in the Wai'anae District is used by the U.S. military. These areas, and others with negative environmental effects that make Wai'anae known as an area of "environmental injustice," are shown on the map. In addition, old military ordinance was dumped off the coast, some of which drifted back to the beach, and Wai'anae is downwind from Schofield Barracks to the east, where depleted uranium has recently been confirmed.

A. An entire valley devoted to Army target practice (Makua Valley)

B. A Navy ammunition depot suspected of harboring nuclear weapons (Lualualei Naval Magazine) and a high-powered Naval Radio Transmitter Facility

C. The island's only landfill (Waimanalo Gulch)

D. A large oil-fired power plant (Kahe Point power plant)

E. An industrial park (Campbell Industrial Park), where garbage-fired and coal-fired power plants are located

Food self-sufficiency has declined steadily. In 2003 it was estimated that the Wai'anae District had only about 200 one - to two-acre family-run "subsistence" farms. The island's last dairy, located in Wai'anae Valley, closed in February 2008. Hawai'i's Food Security Task Force listed Wai'anae as the state's most "food insecure" area, with about 33% of households lacking the "ability to acquire food that is safe and nutritious in a socially acceptable way." This is due not only to the absence of gardens but also to poverty, which stands at over 20% in the Wai'anae District. There are few employment opportunities, and a large homeless population. One newspaper article characterized the coast as "16 miles of ramshackle tents packed with scores of bedraggled kids, women, men, mutts and their remaining worldly possessions." A poor diet leads to poor health, and Hawaiians suffer the highest rates of heart disease, cancer, stroke, and diabetes in the state.

Teaching Hawaiian language in the schools was banned shortly after the overthrow. The education system instituted in Hawai'i is basically an exact replica of that of the United States. It is poorly suited to the cultural and ecological setting, making local students feel bored and alienated. The high school drop-out rate is high at Wai'anae, and few students go on to college. According to the MA'O website, Wai'anae has the state's highest rates of teen pregnancy, school suspensions, incidents of substance abuse, and juvenile arrests.

The negative tip and its ramifications are summarized in the following feedback diagram.

Positive Tipping Point

There have been a number of initiatives to improve the ecological, social, and economic situation in Wai'anae. One of the more recent of these is the Wai'anae Community Re-Development Corporation (WCRC), a nonprofit organization formed in 2001. All members of the WCRC's Board of Directors are Native Hawaiians who live in the district. They are guided by five principle values:

- Ea (sovereignty): To build on individual and community assets to create new local jobs and local businesses, increasing our capacity to be self-sufficient;

- Kako'o (support): To provide diverse experiences and opportunities, which mentor, educate and employ, where creativity and expression are nurtured;

- Kokua (help): To promote diverse cooperative approaches to work and business that build community connections;

- 'Ohana (family): to work with the entire 'ohana for optimum individual, family and community health; and

- Ho'omalu (make peace): To encourage and live by Hawaiian values which build a peaceful community.

According to the MA'O website, WCRC's goal was:

to build a strategy that would impact five critical areas of need: out-of-school youth, sustainable economic development, agriculture, health, and Hawaiian culture. Youth leadership and social enterprise development became our core objectives, with strategies to build a localized movement to put the value of aloha 'aina [love of the land] into action. [emphasis added]

WCRC's chief project is the Mala 'Ai 'Opio Community Food Security Initiative. Its two main components are an organic farm and various educational programs. The project got off the ground with grants from the Bank of Hawai'i, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (Native American program), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Currently grants make up 40% of MA'O's budget; sales 40%; and donations the other 20%. This is expected to change as sales grow.

The Farm

The farm comprises 5 acres of land leased from the neighboring Community of Christ Church. According to Aila, the location was chosen when the church came before the Wai'anae Neighborhood Board to request a zoning variance for expanding its camping activities. It was pointed out that the land is zoned for agriculture. At the same time, WCRC was developing its vision of an organic farm. It was decided to lease the land to the farm. This is a particularly good location because the property is connected to the county's water supply system so, although the bills are rather high, the farm has a steady supply of irrigation water.

I visited the farm on one of its monthly G.I.V.E. (Get Involved Volunteer Environmentally) days (the last Saturday of each month). I heard about it through an announcement from Envision Hawai'i (, a group of "young civil servants and social entrepreneurs." Many other groups from outside the community provided enthusiastic volunteer laborers that day - including the Girl Scouts, a group of Japanese students, the University of Hawai'i, and the Kapi'olani Community College service learning project.

Neat rows of various types of lettuce, mustard and collard greens, oriental cabbages, herbs and spices, beets and radishes, kale and chard, and assorted eggplants grow next to a line of trees laden with mangos, lemons, limes, oranges, and tangerines. This biodiversity is the key to pest control, according to Farm Manager Gary Maunakea-Forth. Unlike large-scale monocropping, the intercropping is less susceptible to widespread damage. The diverse environment provides habitat for beneficial insects (e.g., those that eat aphids), as well as for birds that prey on pest insects. Maunakea-Forth has also learned to avoid growing crops like tomatoes and cucumbers, which are especially vulnerable without the protection of a greenhouse.

Lualualei is blessed with a naturally rich vertisol soil unique to the area. Sun hemp is planted as a rotation crop to replenish nitrogen in the soil. Fertilizers include manure from a nearby dairy (a source which will, unfortunately, soon disappear because the dairy has shut down), as well as bonemeal and bloodmeal from a rendering plant at Campbell Industrial Park. It also includes wood chips and coconut husks from local tree trimmers - a considerable volume of organic matter which, according to Maunakea-Forth, would otherwise end up in the landfill. (My job on G.I.V.E. day was to spread this mulch around with a rake.)

In 2003 MA'O opened Aloha 'Aina Café on Farrington Highway (Wai'anae's "Main Street") to serve its delicious, nutritious produce to the local community. For about two years the business was great. But - according to Maunakea-Forth - it required too much time and effort. Plus, people complained about the lack of air conditioning. When he assessed the cost of installing air conditioning, he found it was just too expensive. (Aila mentioned also that the landlord wanted to raise the rent.) So the café closed.

Maunakea-Forth admits that "we're caught between what can sustain the farm financially and what produce is popular locally." Few local residents have acquired a taste for items like arugula and red Russian kale. And they need to be better educated on the benefits of eating organic, locally grown food to justify spending a few extra cents, said Aila. MA'O sells some of its produce at Tamura Superette, Wai'anae's largest grocery store, and some to nearby Makaha Resort. The bulk of its produce is sold in the city of Honolulu, some 40 miles away - at small health food stores, upscale restaurants, and the Kapi'olani Community College Saturday farmers' market. Demand in the city will soon increase, since MA'O was chosen as a supplier for the first Hawai'i location of Whole Foods Market, the largest U.S. natural foods supermarket chain.

The future for more local "community food security" looks bright, however: Thanks to a grant from the Legacy Land Conservation Commission, MA'O plans to purchase an adjacent 11 acres, land that was once a chicken farm. Efforts are underway to start up a Wai'anae farmers' market, complete with equipment that accepts EBT (i.e., electronic food stamps). And the restaurant at Wai'anae Coast Comprehensive Health Center is expected to provide an additional local market.

Education Programs

Just as important as growing food is growing the youth of Wai'anae "who, owing to a lack of economic and educational opportunities close to home, are often labeled as 'at risk,'" according to Stu Dawrs. MA'O provides staff and support for various intermediate school, high school, and college programs. Students reconnect to the land by learning how to grow and cook food.

Intermediate School

MA'O offers three programs for students of Wai'anae Intermediate School:

- 'Ai Pohaku Workshop ('ai pohaku refers to a taro-pounding stone, or to stone eaters as in the song praising those who loved the land and refused to pledge allegiance to the new government in 1893). This is a culturally-based curriculum for all 7th graders. The students cultivate and harvest food in their "edible schoolyard," a half-acre organic garden. They make poi (mashed taro root), carve traditional implements, and share research information from classroom instruction, assigned readings, and lectures. It is a "mini-immersion" into Pacific Island culture. The workshop is held every Friday for 9 weeks.

- 'Aipo (short for 'Ai Pohaku) and Kalo (taro) Explorations. A 3-week afterschool program. Students participate in five activities: making poi, working in the garden at the intermediate school and at MA'O Farm, visiting Makaha Valley, visiting the taro fields at Waiahole, and a Family Night Dinner and Sharing. Plans are to add a family garden day as well.

- Summer Garden Club during the 7 weeks of summer vacation, in which students meet one day per week from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. to "grow and eat food, study organic farming and learn Hawaiian cultural practices." Each session ends with a big Family Night Dinner.

- An afterschool volunteer garden club that runs nearly the whole school year.

High School

In collaboration with Wai'anae High School's Natural Resource Academy's agriculture program, MA'O helped establish an on-campus certified organic garden. It is the first public school in Hawai'i to have an organically certified garden. In addition to working in the garden, students participate in labs, field trips, and classroom activities. They have also "developed creative entrepreneurial ways to share their veggies with teachers and families, helping to spread awareness and aloha [love] for eating organic." The garden's produce will be featured at the new Wai'anae farmers' market under the brand name Ka'aihonua (food of the earth).

Every spring about 15 Wai'anae High School students participate in a paid Internship in Organic Agriculture and Food Systems, working at both the school garden and MA'O Farm. Besides learning about farm work and entrepreneurship, they also learn to cook the food ("an important part of making the connection," says MA'O Director of Education Summer Shimabukuro). In addition, students have the opportunity to travel to conferences, e.g., the 2006 Hoea Ea Conference in Hilo.

Every summer, about 30 high school students participate in the "ramp up" college program. According to Shimabukuro, this is a "boot camp" to prepare for the college internship. Students work on the farm and develop good work ethics (e.g., showing up on time and calling in if they will be absent). They also prepare for college with a summer course that tests and improves their reading, writing, and math skills.

College

Perhaps most exciting is MA'O Farm's 2-year Youth Leadership Training (YLT) College Internship program, which offers Wai'anae youth an opportunity to start their college careers with an Associate of Arts degree from Leeward Community College. Each semester 12 to 18 students are enrolled in the program. They work on the farm Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays in various capacities, including management. According to Kainoa Aila, the typical work day starts at 7:00 a.m. with a traditional Hawaiian chant. Then comes briefings and work assignments. Students plant, weed, fertilize, and water the crops. They pick, wash, and package them for delivery. Usually they set out for town at 1:30 and return at 5:30 or 6:00 p.m. Early Saturday mornings they set up a booth at the busy farmers' market at Kapi'olani Community College. It is a fun way to practice entrepreneurship and customer service skills. On the morning I visited the market, one young man was checking off inventory on his clipboard while two young ladies smiled and offered free samples to shoppers. The $4 bags of Sassy Salad - MA'O's signature blend of baby greens - are a very popular item.

In Fall 2006 the program became an official for-credit certificate program at Leeward Community College. The students take courses such as "Introduction to Organic Agriculture," "Hawaiian Studies," "Entrepreneurship," and "Native Nutrition and Lifestyle," as well as communication skills and financial education for their certificate in community food security, in addition to basic courses required for an Associate of Arts degree (60 credit hours in total).

The students also host and attend conferences on food security and sustainability. The MA'O website lists the most recent of these under the heading "Building a Youth Movement":

- Hands Turned to the Soil, Wai'anae, Hawai'i, May 2005

- World Indigenous Peoples Conference on Education, Hamilton, New Zealand, November 2005

- Community Food Security Coalition Annual Conference, Vancouver, Canada, October 2006

- Community Food Security Coalition National Farm to Cafeteria and Food Policy Conference, Baltimore, Maryland, March 2007

- Food and Society Conference, Traverse City, Michigan, April 2007

- Ho'ea Ea - Return to Freedom, Hilo, Hawai'i, June 2007

- 2050 Youth Sustainability Summit, Honolulu, Hawai'i, September 2007

The YLT students receive a stipend of $500 per month during their first year and $600 per month during the second year. They also receive full tuition scholarships, and a savings plan in which MA'O will match every dollar saved with an additional two dollars. According to Maunakea-Forth, most students use the savings to buy a computer. One student, Tiana Lopes, will use her savings to study Permaculture in Brazil as part of Amherst College's "Living Routes: Study Abroad in Ecovillages" program. It is expected that two students will graduate from the program in Fall 2008, and an additional four in Spring 2009. Most intend to move on to the University of Hawai'i for higher degrees in various fields (education, communications, Hawaiian Studies).

Some quotes from the website and articles convey the impact on students' lives:

"I've learned so much here, and not just about farming. I've learned about nutrition, being part of a team of workers and, when I'm in the field picking, what real peace of mind is."

- -Rachelle Carson, college intern"I'd hate to imagine what my life would be if I hadn't of joined 'Ai Pohaku in 7th grade. It has given me the opportunity to travel and help other people build lo'i (taro patches). I can't explain how it makes me feel, like when I work in the lo'i it just feels right, like this is what I'm supposed to be doing, this is where I'm supposed to be."

- -Tashja Tong, LCC student"I never thought I'd be a farmer. But since joining MA'O, my perspective on agriculture has totally changed. Being an organic farmer is one of the most important jobs in our community and I take pride in training to be one for a career."

- -Manny Miles, Farm Manager Apprentice

This is still a tipping point in progress. Asked about his assessment of MA'O as an "EcoTipping Point," Maunakea-Forth said some of the youth have started gardens in their own backyards. The upcoming expansion of the farm, and of its market to Whole Foods, are promising, as is the upcoming Wai'anae farmers' market. But we need more people to "jump on the bandwagon" of homegrown organic food, he says. Agriculture in general needs to be taken more seriously as an economic sector (versus tourism and the military); something must be done about the high price of land, and farmers must be able to obtain long-term leases. Some help came from the 2008 state Legislature and the County Council, which passed a number of bills to promote local agriculture with tax credits and loan programs.

Aila estimates that an additional 11,000 acres of land controlled by the military and 1 million gallons per day of water could be made available for agriculture in Lualualei Valley. I asked him about the possibility of allowing the homeless to grow food on part of MA'O's new 11 acres. He said it is a good idea, if they could form a cooperative to make use of the tractor.

On another promising note, the Department of Hawaiian Homelands has named Agricultural Production and Food Security one of its priority projects in the Wai'anae area, with MA'O Farm as a potential partner.

Of course, just as important is the beneficial effect on Wai'anae's youth. Hawaiian students whose curriculum includes hands-on outdoor activities and cultural learning are able to reconnect to the land. They are more engaged at school and less likely to drop out. The income and scholarships provided by MA'O give them opportunities that might otherwise not be available. According to Bushley,

MA'O's true strength derives from its focus on youth empowerment, which has created a ripple effect in the community, promoting an awareness of a need for broader self-sufficiency and local empowerment. Although Gary and Kukui [Maunakea-Forth] serve as the inspiration, the youth are the engine that drive MA'O's vision for a healthier, more cohesive and more secure community.

The positive tip and its ramifications could be diagrammed as follows:

References

Aila, William Jr. 2008. Interview with Manny Miles and Kainoa Aila. Website http://vids.myspace.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=vids.individual&videoid=28790022

Bushley, Brian. 2007. "Growing Organic Leaders Through Youth Empowerment: MA'O Farms and a Vision for the Future of Wai'anae." Transformations in Leadership 1(1), p. 1-6.

Cordy, Ross. 2002. An Ancient History of Wai'anae. Honolulu: Mutual Publishing.

Dawrs, Stu. 2003. "Into the West." Hana Hou Magazine 6(5).

Fogle, Jacquie. 2007. PowerPoint presentation for UH Interdisciplinary Studies 489 and the EcoTipping Points Project.

Food Security Task Force. 2003. Report to the Legislature on SCR 75, SD1, HD1, 2002. Website http://hawaii.gov/dbedt/main/about/annual/2003-sfstf.pdf.

Hoover, Will and Rob Perez. 2006. "Wai'anae's homeless just can't afford to rent." The Honolulu Advertiser, Oct. 15.

Kakesako, Gregg. 1998. "Lualualei." Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Oct. 5.

MA'O Organic Farms website: http://www.maoorganicfarms.org

McGrath, Edward Jr., Kenneth Brewer, and Bob Krauss. 1973. Historic Waianae. Honolulu: Island Heritage.

Ryan, Tim. 2008. "Ma'o Farm." Edible Hawaiian Islands, No. 4, p. 11-13.

State of Hawai, Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism. n.d. Wai'anae Ecological Characterization. Website http://hawaii.gov/dbedt/czm/initiative/wec/index.htm

State of Hawai'i, Department of Hawaiian Homelands. 2008. Waianae and Lualualei Regional Community Development Plan. Website http://hawaii.gov/dhhl/publications/regional-plans/o-ahu-regional-plans/Waianae%20Regional%20Plan%20January%202008.pdf.

Sullivan, Claire. 2008. "Saving Hawai'i's Farmlands." Honolulu Weekly, Feb. 13-19, p. 6-7.

Wai'anae Coast Comprehensive Health Center. 1991. The Wai'anae Book of Hawaiian Health. Wai'anae: WCCHC.

Wu, Nina. 2007. "Whole Foods names first isle farmer partnerships." Honolulu Star-Bulletin, July 14.

Wu, Nina. 2007. "Whole Foods deal is growth opportunity." Honolulu Star-Bulletin, July 24.

Personal Communications (with thanks)

William Aila, Jr., MA'O Board of Directors

Vince Dodge, MA'O Intermediate School Program Coordinator

Judy Kappenberg, Leeward Community College

Gary Maunakea-Forth, MA'O Farm Manager

Summer Shimabukuro, MA'O Education Director

Este sitio web contiene materia traducida del sitio web www.ecotippingpoints.org.

Traducción: David Nuñez. Redacción: Gerry Marten