EUA - Utah (Salt Lake City) - Planificación Regional mediante Participación Comunitaria: Aprendiendo de Envision Utah

- Autor: Gerry Marten

- Esta historia detallada está basada en una visita de campo realizada por Gerry Marten y Steve Brooks a Envision Utah en Octubre del 2005

- Apuntes de la entrevista de Steve Brooks

- Recomendamos ampliamente el dictamen Envision Utah: Producing a Future for the Greater Wasatch Area. Descargar pdf (37 mb)

A mediados de los 1990s la región de Salt Lake City, un área de 98 municipios y 1.8 millones de habitantes, estaba impulsándose hacia la dispersión urbana. Pero en 1997 una coalición pública/privada conocida como Envision Utah fue formada, poniendo en marcha un proceso que cambió de manera drástica el crecimiento urbano en la región. La historia de Envision Utah demuestra no solo que el crecimiento urbano puede ser canalizado de manera saludable, sino que nos muestra como hacerlo.

Envision Utah started with a regional visioning and planning process during 1997-1999. The way they did it set the course for success:

- They employed a small professional staff to manage the process.

- They contracted Calthorpe Associates (Berkeley) and Fregonese-Calthorpe Associates (Portland) to facilitate. Calthorpe offered a unique map-based workshop process, coupled with Geographic Information System software to generate alternative growth scenarios (including freeway and mass-transit corridors) and rigorously assess the consequences of each scenario with respect to what the region's people wanted for their future.

- They used the workshop process to draw heavily on citizen input, beginning with a broad spectrum of influential citizens from business, government, and public stakeholder groups. They then extended the workshops to thousands of citizens throughout the region. Over the two year planning period, there were several hundred workshops involving a total of 18,000 citizens.

Envision Utah kicked off the planning process in 1997 with an intensive study to clarify what people in the region considered most important for their future. The resulting "values framework" was the driver for everything that followed.

In 1998 the focus shifted to workshops that examined how to accommodate the one million additional inhabitants expected in the region by 2020. There were typically 200 people at each 3-hour workshop, ten people to a table. At each table there was a map and chips representing particular elements of urban growth to be placed on the map. In a progression of workshops over the year, participants used maps and chips to explore different kinds of development, various neighborhood designs, and where they should be located to accommodate the 2020 population. At the end of each workshop, results from each table were shared with other participants and recorded for future use.

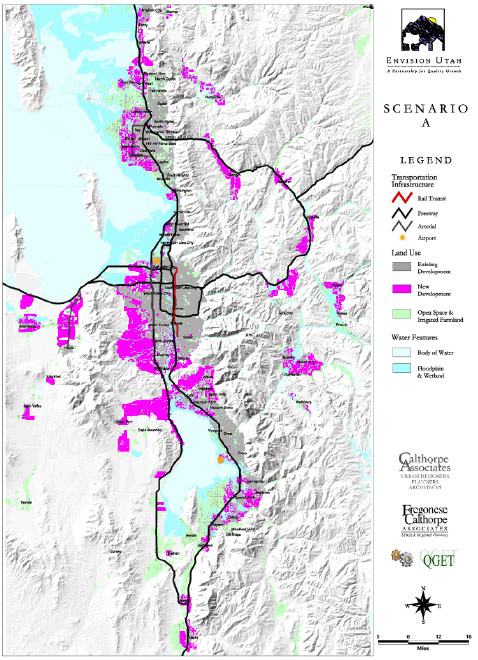

Envision Utah used the results from all the workshops to extract four representative scenarios. Scenario A represented "business as usual." Scenario D featured walkable communities with nearly half the development directed into existing urban areas. Scenarios B and C were intermediate. For each scenario, Envision Utah prepared a composite map based on results from the workshops, showing where each kind of development should be located. They also prepared bar graphs comparing each scenario with respect to "indicators" that connected directly to the public "values framework." For example, the indicators included quantity of new land development, infrastructure cost, water use, traffic flow, and air pollution. With 47 town meetings and a newspaper supplement that reached 570,000 people, Envision Utah solicited public response to the scenarios and key issues that emerged from the workshops. An informal vote from the public revealed a strong preference for scenarios C and D.

During 1998, there was another round of public workshops to mold the most desired scenarios into a "Quality Growth Strategy."The Strategy included 47 development goals, each specified with respect to who should be responsible for implementation and how to do it. There were also detailed maps showing where different kinds of urban growth should be located. The Quality Growth Strategy became state law at the end of 1999. Stakeholders from fiscal conservatives to environmentalists supported the Strategy because it addressed common ground of concern to all. The Strategy didn't dwell on restrictions to growth. Instead, it broadened development choices to allow the kind of growth that people really wanted. Detailed Envision Utah: Producing a Future for the Greater Wasatch Area report on the process during 1996-2000. Download pdf (37 mb).

In 2000, Envision Utah followed the planning with a 280-page "toolkit" manual on how to implement the Quality Growth Strategy, conducting training workshops for 5,000 people in both public and private sectors. Following up on delineation of transportation corridors during development of the Strategy, Envision Utah conducted a series of citizen workshops to elaborate the details. Most developers have bought into the new development style, and initiatives on their part have been at the forefront of implementing the Strategy. Particularly notable is Kennecott Land, the largest land owner in the region, which has demonstrated its commitment to developing 90,000 acres during the next several decades in complete accord with the Strategy.

Envision Utah continues to assist municipalities with the ongoing process of implementing the Strategy, and many municipalities utilize map-based citizen workshops to do it. Most development is now "filling in" instead of sprawling out, and most agricultural land and other open space remains intact. The Strategy has substantially reduced local energy consumption and infrastructure costs and improved the region's competitive position for federal infrastructure dollars. Light rail has become a routine part of the transit scene. Ridership is now three times originally expected, and more lines are added every year.

Other metropolitan regions have embarked on this process with comparable success. Experience with the process, from workshops to media publicity, the technical capacity for scenario mapping and indicator assessment, and the speed of doing it all have come a long way since Envision Utah's pioneering effort in the late 1990s. A report from the Austin region (Appendix IV: pages 58-81) Download pdf (29 mb) provides an impressive illustration of what is possible when comparing growth scenarios with regard to indicators such as public and private transportation costs, traffic flow, commuter travel time, fuel consumption, air quality, public costs for new infrastructure (e.g., roads, water supply, sewage), water consumption, urban watershed runoff, loss of agricultural land, green space, and affordable housing. See Appendix C

References

- Envision Utah, Calthorpe Associates, and Fregonese-Calthorpe Associates. 2000. Envision Utah: Producing a Future for the Greater Wasatch Area. 83 pages. Download pdf (37 mb). This report provides a complete account of what happened with Envision Utah during 1996-2000, including complete graphics for scenario maps and other results.

- Peter Calthorpe and William Fulton. 2001. The Regional City: Planning for the End of Sprawl. Island Press. Pages 126-159.

Notes from Envision Utah Interviews (October 2005)

Autor: Steve Brooks

Interview with Ted Knowlton (Planning Director, Envision Utah)

By 1995, Utah was experiencing an unprecedented growth spurt, and new worries about how growth would affect Utah's quality of life began to emerge. The climate prompted the Coalition for Utah's Future, Envision Utah's parent organization, to start the Envision Utah project. The net effect of Envision Utah's efforts has rippled outward to fundamentally change the dynamics of growth and planning in Utah.

The catalyzing power of Envision Utah rests in the process it uses. Envision Utah involved 18,000 residents in the creation of an alternative vision of the region's growth and transportation, known as the Quality Growth Strategy [Link], the "tipping point" in our region away from unsustainable growth patterns.

Envision Utah has facilitated an inclusive process from the beginning. By being open to all potential stakeholders, even those who oppose some quality growth efforts, Envision Utah has been able to find common ground among the different groups and create dialogue on growth issues in a state where the overriding political climate is heavily pro-property rights and distrustful of government efforts including planning.

Because it uses a bottom-up, inclusive process, almost all of Envision Utah's Quality Growth Demonstration Projects have left alliances in their wake. New partnerships have occurred among existing civic organizations, such as the state's two largest metropolitan planning organizations.

The Quality Growth Commission is a new civic institution. The largest Metropolitan Planning Organization now has a Regional Growth Committee and an Open Space Committee. The Envision Utah Governor's Quality Growth Awards, which have honored 38 private and public achievements, is another example of a new civic institution.

Don't feel the individuals who started Envision Utah felt they were in the midst of a vicious cycle. I do. It started with the I-15 freeway - sprawl, decline of central cities, more I-15 and more sprawl. High vacancy rate in office buildings, disinvestment, number of neighborhoods decreasing in population.

More emphasis on sprawl - long commutes put pressure on families. Congestion, feeling they're losing the feel of a smaller Western metropolis. It became a big city. Farmland being gobbled up and paved over. Sprinkle a little bit of housing into farmland, land prices rise. Get a pioneer subdivision - the second they go in, they start complaining about farm noise, smell. Local government passes a nuisance ordinance against farmers. Need a critical mass of farms to support ancillary businesses like feed stores.

Robert Grow and Steve Holbrook were the architects of Envision Utah. Grow was an attorney, runs a law firm branch.

They wanted to bring about attitude changes on issues and disseminate solutions, especially at the local government level. Studied Denver and Portland for ideas. Concluded you have to lead people to this slowly. There was a public involvement effort without a set of solutions on the front end.

The workshops were similar to what had been done in Chicago, Denver, Los Angeles and Jackson Hole. It's my understanding that, left to their own devices, people chose redevelopment and light rail. These workshops were 2 ½ hours. "Chip Games" - Detail is in how many chips, complexity of types. Local planners are not used to looking at regions - it's taking them out of their comfort zone. There were three levels - region, subregion, neighborhood. Most people understand the whole county or within 10 miles of their home. The more you zoom in geographically, the more you can have people think of their shopping area. Our Metro area was a string of valleys with their own boundaries.

Where most people wanted Salt Lake to go was very different from where it was going. When you work with a neighborhood, it's a challenge to get people to think regionally.

They knew they needed to develop scenarios and to involve the public before they developed scenarios. Who was involved - city councilors, mayors, prominent developers were involved. It was for them to see each other responding the way they did was fundamentally reinforcing the idea of a different direction. People will comment how electric it was, how light bulbs went off. Who was there, it was decision makers, people who could do something about it. Local governments picked representatives.

They were taking local leaders, creating a common vision, educating them, getting them to be evangelists.

The parent organization, the Coalition for Utah's Future, existed before, for 3-5 years. They were exploring issues like public lands, health care, early childhood education. Any issue that affected quality of life.

The Olympics made people feel a growth boom was going to hit us over the head. It forced a lot of leaders, especially at the state level, to think about our shortcomings of infrastructure. The plan for 20-year growth, they had to make it happen in 7 years. It got people in a mindset of thinking about growth.

If the exact same process were to happen today, with the same set of attitudes, it would not be as successful. It was the right process at the right time.

The transit emphasis has tangibly changed. Public transportation was considered just for the poor in 1995. Now, literally every community is clamoring to get light rail if they can. Now planning departments are spending 1/3 of local transportation dollars on public transportation capital investments.

It doesn't immediately deter sprawl, but it sets up a dynamic where it inspires transit-oriented development. Using public transit investments to bring about reuse of underutilized land.

The location of light rail through old existing communities, a lot of land near the stations was underutilized. It doesn't require new roads. It's further development of what's already developed.

When you have a substantial enough transit system, redevelopment can reduce auto dependence overall.

Construction of our initial light rail line was a "tipping point".

Smart growth advocates in the university before Envision Utah had to hold their tongues. They were considered radical. We moved smart growth nomenclature to be the moderate position. It's the hardest to quantify and most significant change. Attitudes have continued to move over time. Peter Calthorpe last week spoke to 125 people including most mayors from Salt Lake County. Afterward, he said "No one needs to be afraid to use the D-word: Density." It enables continued investment in existing communities. The original pioneer municipalities were stagnant. Multi-use developments improved quality of life.

After the workshops, we developed a toolbox of planning ideas and an aggressive campaign to train local officials and planners. The document had some New Urbanist concepts: cluster development, walkable communities, encouraging transit ridership through land use and zoning strategies. We trained 5,000 people. Some percentage stayed public officials or Envision Utah-ites found themselves in places of power.

60 percent of the communities adopted changes in their ordinances along Envision Utah principles. A smaller number adopted holistic change to community ordinances.

Developers were invited to training sessions, as well. 2/3 of developers view us as allies. Those who profit off conventional development, some percentage are worried about us. It mostly requires policy changes.

An anecdote: I just worked with Brigham City to revise their general plan. Development will hit them in 10 years. We don't use the words New Urbanism and Smart Growth. We say "walkable communities." A planning commissioner stopped and said how excited he was by the new document. "It seems to be good for business. It seems to be something that tries to help us succeed." It loosens up land-use regulations in exchange for more flexibility of design. You care 95 percent about where things go, you don't care what they look like. You just change your emphasis. You see a light bulb go on in people's minds.

This is as Republican as it gets. You can paint so many of these ideas in a conservative way of viewing the world. Like a requirement for a high amount of parking areas is constraining development. Lowering parking requirements –20 percent of parking in a standard shopping center is used only 8 hours a year.

We want local governments to get out of the way of the market on densities. They're constraining the market on density. There's a percentage who view it that simply. Sometimes we hear the names of developers who are invoking the name of Envision Utah. But density by itself is not what we're talking about. Density is good if it's walkable, coupled with opportunities to ride the train or bus. Ugly density in marginalized parts of town is bad for residents and regions.

The Legacy Highway - a proposed highway in Davis county. The Utah Department of Transportation was counting its chickens before they hatched. They hired a contractor and started paying before the Environmental Impact Statement was approved. Opponents took them to court. They hadn't considered alternatives. Opponents won, delayed the Legacy substantially, won a number of concessions. Then the DOT looks at a major corridor in Western Salt Lake County. To avoid the same fight, they decided to team up with us. We worked with 13 communities on alternatives to the land use plan. We used transit as a means to a higher transition. DOT assumed that land use would be the same as traditionally. There are a handful of cases nationally where you have a major EIS that explored alternatives.

The Mountain View Corridor - What it led to is potentially a smaller freeway. No desire of those people to kill the freeway. But higher-quality forms of public transit than would otherwise have happened. If they don't change land use, they're likely to get busses out here. With a series of transit-oriented developments, it would take 10 years for transit to get there.

Commuter Rail - heavy gauge - runs infrequently, except at rush hour. Light rail - planners think of streetcars as light light rail. Streetcar system you don't have to displace a lot of utilities. In our region we will use commuter rail like light rail. In regions like Chicago, commuter rail facilitates sprawl. Commuter rail is capable of speeds of 80 mph. The stations are further apart. Not the same acceleration as light rail.

Metropolitan Planning Organizations - two serve our metro area. Official regional transportation practice has been to take general plans of communities as a fixed input and plan for transportation based on that. It's a totally vicious cycle.

Wasatch Choices 2040 looks at different land use ideas and how they fit with transportation ideas, how they affect quality of life. It will lead to fundamental changes at the MPO level about how they make funding decisions. Now they will use a set of adopted growth principles. The old principles were congestion reduction. Outcomes of this process, the land use scenario used for the next long-range transportation plan. Land used from a vision rather than a projection.

You're the community. You can still make wrong decisions. But you will be knocked down the priority list. Wasatch Choices - strong support for transit, mixed used development, more chips on developed land.

History - light rail was up and running two years after the Quality Growth Plan. How have land use plans changed? A couple of transit-oriented developments are under development, several more in planning stages. A handful of communities believe in it completely. Murray, Midvale, Sandy and SLC.

Envision Utah is a nonprofit. We increasingly do local fundraising. National foundation money has dried up. Clients often pay for our services. We worked with Sandy City paln for historic neighborhood at a lite rail station.

West Bench - Kennicott Land is the landowner. Calthorpe is a consultant. It's one gigantic New Urbanist project. They're just developing parts that are pretty flat. The intensity is the same, focused around mixed use, walkable developments focused on the least environmentally sensitive land. Kort Utley - head of Kennicott Land Co.

Responsible development here has helped them get authorities to permit mining in other areas. It shows they can reclaim the land. Rio Tinto the parent company. It costs more to develop up front but appreciates more over the long haul. They started about five years ago.

West Bench is one of the major ways Envision Utah has made an impact. But Kennicott can say it couldn't have happened here without Envision Utah.

There are a number of small projects throughout the region and a handful of plans approved. "I feel we're on the cusp in this region."

Environmental concerns - air quality, decreasing development on critical lands (steep slopes, critical habitats), reducing demand for future water sources - all are tied to land consumption.

What we learned from an in\depth analysis of Utahn's values is pretty generalizable across the country. Selling smart growth on principles of benefiting ecology isn't that valued. They don't care much about fish and wildlife, but they do care about recreational opportunities. We're making sure we save those places for us to play in.

Peter Calthorpe says there are two things distinctive to this area. 1) Willingness to collaborate. 2) Concern for future generations. Those two dynamics transcend politics.

We had a retreat with our board. Michael Young said, You give the same nucleus of information to people, they tend to reach the same solutions. There's magic in looking far enough ahead that you're not looking at today's battles.

Interview with Steve Holbrook (Envision Utah's first Executive Director)

Coalition for Utah's Future has been around since 1990. Project 2000's predecessor. A committee of KUTV Channel 2, the Hatch family. Produced 20 documentaries on growth and Utah's future.

Scott Matthesson, ex-governor, formed a coalition.. They looked for stakeholder investment. They did projects on childcare, healthcare, after-school programs, wilderness designations. Figure what you can move on together.

1995 to 1996 - Utah's economy started bouncing back.

Equity refugees from California, sold their houses in California and bought cheaper ones here. It was very noticeable here.

Decision to rebuild I-15. Closing it down through most of the construction period, gave us a sense of being crowded.

Brought in Robert Liberty, 1000 Friends of Oregon. Interviewed 150 local leaders.

Former Governor Kevin Rampton - in early 1970s, Utah passed land use law much like Oregon's It was repealed at the behest of homebuilders and radio talk show hosts. Rampton later said he had made a mistake not involving homebuilders.

Mike Leavitt remembered the story of his father running for governor. He had voted for the land use law in the state senate. So Leavitt would say, "Planners - aren't those the people who come and tell you can't put a room in an attic?"

But he sponsored a growth summit after they decided to rebuild I-15. We created the first stage idea of Envision Utah, the four scenarios and the Quality Growth Strategy [[Link to Appendix: Envision Utah Quality Growth Strategy at bottom]]. Calthorpe was willing to create a hybrid approach with our committee. 200 people at the core, partners and special advisors. Robert Grow was the inspiration and the idea person. Big ideas came from Robert. He had a position and enough political contacts that people like the governor had to listen.

The governor turned us down at first. He learned as he went along. He sat at the first regular stakeholder meeting. When we did the baseline, he looked at it and said, "We can't afford to do all of this!" It was the first time anyone had pulled all of this together.

One piece of information was that the vast majority of growth would come from our children and our grandchildren. Before that, we thought it was the Californians coming. People felt this was happening to us, not, we're doing this for ourselves.

The very first set of workshops, we held 50 workshops in 2½ weeks. Calthorpe didn't participate. He modeled the output of 200 regional stakeholders. I was the one promoting broader involvement with communities.

Apart from gathering information about what people think, it's highly informative for the people who participate. Some would say this land should all be park. A city councilor would say, "Who's going to buy it?" Someone else would say, "I'm a developer. I want to develop this land." They would design something that tried to accommodate everybody else. People would tend to come up with practical solutions to problems.

We would show the baseline before everybody sat down. Doing the process like that forces people to move from philosophizing to problem-solving. Because you're looking at twenty years, it moved people away from conflicts of today. Longer out, there's more commonality. It's easier if you haven't just made the decision.

A big issue was the Legacy Highway. We refused to get involved. This is a small project. We're out of today's fray.

Calthorpe did the land use modeling. We created strategies. We did the same stakeholder process with 90 different strategies.

The first thing we did after the growth strategy's release, we had a series of transit-oriented development workshops. Thirty communities had potential for it. We hired Fregonese to run the meetings. Communities did their own workshops to design transit-oriented developments.

Several hundred workshops the past 10 years. Advice - don't do so many. You have to target what you want the public to respond to. Every time the participants dropped by half. People come in not expecting to have a good time. It's very interactive. People are saying, "This should be here." Your task is to come to consensus. We devised a customized set of maps and chips for each workshop. Computers were a very expensive alternative and reduced the number of people who could play. There's something about Monopoly –you're talking to each other, not staring at a computer.

There was no political entity that was the recipient of the original plan. The idea was sort of to get everybody to think.

For the Greater Salt Lake Shorelands Plan, we brought 9 communities together on the shores of the Great Salt Lake. The Shorelands plan was put into the long term plans of all 9 communities.

Tooele County took 50 percent of all developable land off the plate. Transfer of development rights. One area a receiving zone, another a sending zone. Developers can buy my development rights and use them somewhere else. Developers can build with a higher density there. Say a property worth $400,000, but the owner can take $200,000 and keep on farming.

The first "tipping point" was the recognition there was not going to be a state land use plan. The process had to be designed around local control. There was a lot of fear among local mayors. The importance of that - not just for Utah - they wanted to implement an Oregon-style approach and were not able to. Wide participation was key. People felt empowered. The sense that we got our say is much greater if we give it before it happens. The problem with most civic processes is they lead to automatic polarization.

Before the workshops, Envision Utah brought together all the media and asked them for help getting the word out that there was a process and publishing the scenarios. For two years, we were in page A-1 and B-1 stories. The general public, even if they didn't show up for meetings, they could follow what was happening.

The baseline - to the man in the street - was that all these Californians were moving to Utah. The starter castles were so visible. But almost 70 percent of the growth rate was the local birth rate.

Salt Lake County had 50,000 Hispanics at the beginning of the '90s, 200,000 by the end of the '90s, 5,000 of whom were legal. In our later processes, we put ads in Hispanic newspapers. I should have gone through soccer leagues to reach them.

Citizen participation was informed by projected reality.

Large families were traditional in Utah. They've been growing smaller over time, incrementally. By making people think regionally, it helped people out of "I've got mine." The process was educational itself. People see that certain kinds of things will have to be dealt with.

It was general concern about growth and its apparent lack of direction. Robert Grow probably was the stimulus, thinking there was something you can do.

At one point, Brad Barber, who was head of the Governor's Office of Planning and Budget. Robert turned to him and said, "What is one thing we could do to move forward." He said, "Do a baseline." But we didn't have funds. Coalition then talked directly to the legislature. They inserted a line item into the budget. They had noticed things were popping. 1996, probably, or early 1997.

The first meeting with the general public was in response to the baseline.

No one knew what to do, because of the 1972 plan.

Traffic was getting heavier, more and more fights in planning commissions. There was general awareness that I-15 was a problem. Growth was speeding up as the economy came back. Utah was in recession from 1988 to the early 1990s. Its bounceback came earlier and bigger than the country as a whole.

How do people experience growth - it's the development you can see. Until the '60s, well-educated Utahns had to leave the state to have careers. Rampton started Rampton's Raiders, to get the ski industry going. "We sell cheap." Growth in California, companies can't afford to live there. Economic growth, as we've diversified employers, people were able to stay here.

The Olympics were a marketing tool to get money to rebuild I-15 and the first phase of the tracks. Our role in the referendum that passed in 3 of the 4 urban counties, for funding the tracks. The acceptance fo promise of transit-oriented development.

Some time, Robert Grow became an Latter Day Saints missionary in Sacramento. We hadn't taken full advantage of the transit system. Not doing transit-oriented development, not all the potential ridership.

Making sure the 200 stakeholders we invited were balanced.

It wasn't till you had specific development types assigned, not just general population numbers. We had a huge room in the American Stores Building, divided people up according to the subregion they were in.

Grow was the chair of our growth committee before he was chairman of the Coalition. When he was on the executive committee, his force of personality. Robert is the kind of person who comes up with 20 ideas an hour. I say we can do three of these.

I'm a community organizer. I was a civil rights worker in the south, anti-Vietnam organizer in Southern Leadership Council. I started KRCL, the community radio station. Served in the legislature three terms.

The coalition was bipartisan, made up of people at the tops of their fields. The first year, I had as my two unpaid lobbyists, a former governor and head of state senate. Got state office of child care. First we got authority for local governments to impose a transit tax. Utah Transit Authority worked the Senate, we worked the House.

They passed a ¼ cent sales tax. A lot of people give us credit.

It took away the idea of empire-building for the Utah Transit Authority. It increased the sense of regional reality. Growth is here and it is us. The sense of cooperation.

Failures - The short term is still driving development decisions. The current system encourages unproductive development. It's not been addressed.

Small strip malls that are becoming outdated are redevelopment opportunities.

Salt Lake County passed an Arts, Parks & Zoo tax, building recreational facilities at a pretty good rate.

You still have limitation of having to do thing community by community.

Ninety cities. Think how often city councils and mayors change. We tried two years ago, we had a renewal meeting to restrategize the key strategies and their order of importance. In part, because of the success of the tracks, people saw public transit as the first priority issue.

Our focus has shifted from broad regional work to local communities. Competition for people's attention.

At some point, a conservative think tank used the Oregon model to attack our work. We did a workshop with realtors to overcome that perception.

A lot of Envision Utah became the Bible, quoted by both Christ and the Devil.

One problem we faced was old technologies by the Wasatch Front Regional Commission. They did some work on transportation. Their old models do not give credence to the benefits of transit-oriented development. Early on, we funded the development of an Urban SIM, a more state of the art modeling technique.

A big contributor to the reduction of emissions the last 15 years was industry. The next big push has to be transportation and cars. It may be cleaner than projected if our strategies are not carried out. People are riding public transit at much greater rates since gas went up. But buses have to raise rates, too.

Appendix A: Envision Utah Quality Growth Strategy

Envision Utah (Quality Growth Strategy): Download pdf (140 kb)

Appendix B: Comparison Of Urban Sprawl For "Business As Usual" And The Quality Growth Strategy In The Salt Lake City Metropolitan Region

From Envision Utah: Producing a Future for the Greater Wasatch Area report: Download pdf (37 mb)

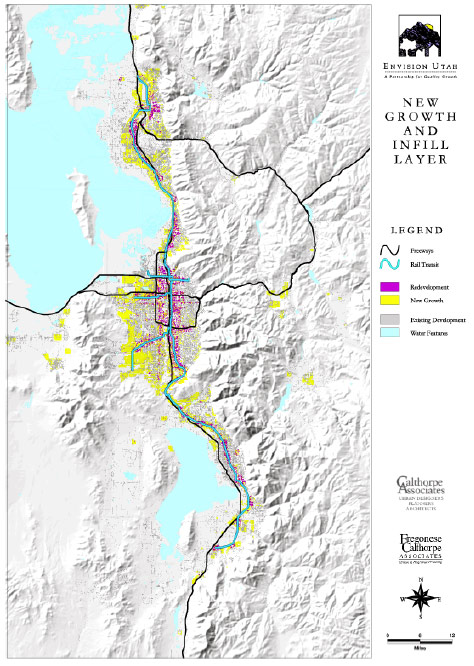

New land development for urban use (magenta) by 2020 assuming a "business as usual" scenario (i.e., continuation of the same urban growth pattern as occurred during the 1990s. (below)

New land development for urban use (yellow) by 2020 assuming a "Quality Growth Strategy" scenario. Magenta indicates redevelopment of existing urban land. (below)

Appendix C: Comparison Of Urban Sprawl And "Indicators" For "Business As Usual" And "Low Sprawl" Scenarios In The Austin (Texas) Metropolitan Region

From Envision Central Texas: Your ideas, Our Regions Future. Download pdf (29 mb)

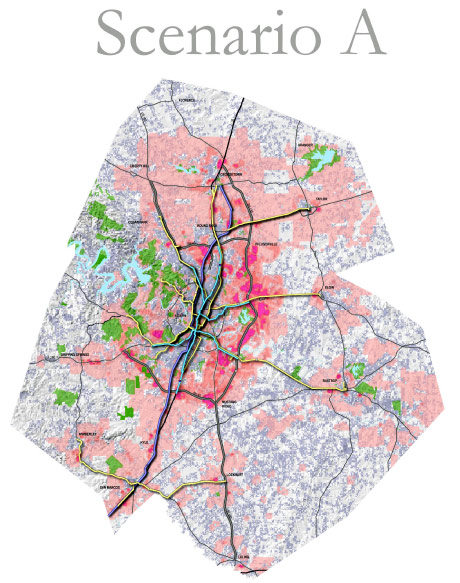

Urban land (red and pink) assuming a "business as usual" scenario to accommodate an additional 1.25 million people in the metropolitan region. (below)

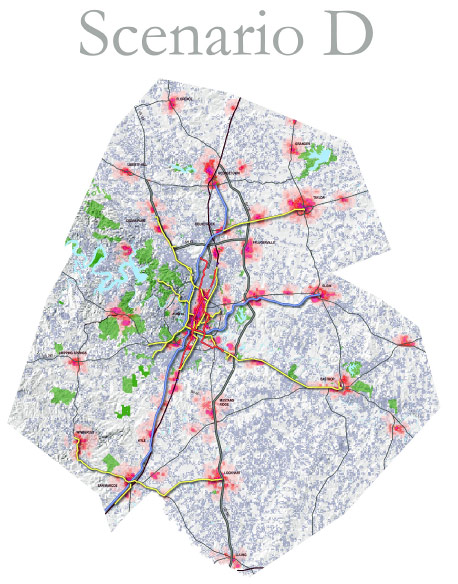

Urban land (red and pink) assuming a "low sprawl" scenario to accommodate an additional 1.25 million people in the metropolitan region.

"Indicators" showing the expected consequences of "business as usual" (Scenario A) compared to a "low sprawl strategy" (Scenario D) - (below)

Este sitio web contiene materia traducida del sitio web www.ecotippingpoints.org.

Traducción: David Nuñez. Redacción: Gerry Marten